In this issue:

- Ant Group and China’s Fitful Convergence

- The Startup Cycle

- Buybacks

- Return-on-Kickback

- Legalization

- Housing

- Big Tech, Monopolies, and Attack Surface

TikTok

Ant Group and China’s Fitful Convergence

Ant Group, China’s largest digital payments company, is preparing an IPO, and has filed an extremely comprehensive draft prospectus detailing their business. Ant is rumored to be worth $200bn ($, WSJ), and plans to sell roughly 10% of its shares to the public, which would make Ant the second largest IPO in history after its partial parent company, Alibaba.

Ant is a revealing look at China’s economic strengths and weaknesses. On the strengths side, China’s consumer Internet companies are absolutely world-class, with faster growth and a far faster shipping cadence than US companies can manage. Ten years ago, this was mostly due to catch-up growth: if you named a major American consumer web category, and bet that a Chinese company would implement roughly the same model and dominate its market, you’d be right.

(A friend of mine once worked for a US-based company that wanted to do a deal with a competitor in China. He met with the CTO of the Chinese competitor, who bragged that his company had copied the US company’s product pixel-for-pixel.)

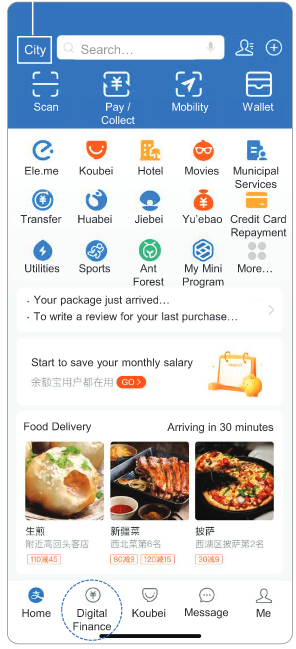

That is definitely no longer the case. Today, Chinese consumer Internet companies ship so many products, so fast, that every American Internet company can be described as implementing a subset of any given Chinese Internet company’s offering.[1] A brief case study in this is Ant’s app:

It’s a payments app, so naturally it gives users the option to (in the order in which they appear in the app):

- Order food on ele.me

- Buy local services on Koubei

- Rent a hotel room

- Buy movie tickets

- Complain to the government

- Transfer money

- Borrow a small amount of money

- Borrow much more money

- Manage a money market fund account

- Repay a credit card

- Manage utilities

- Do something involving sports

- Track low-carbon activities like walking instead of driving, and get credits that can be turned into a virtual forest, which then turns into an actual forest. (As of 2017, 200 million people have tried this.)

- Find other mini apps

Clearly, Ant’s business is focused on the narrow, well-defined market of a) money, and b) goods and services that can be purchased for money.

Ant’s main business, in terms of gross volume, is payments. In the last year, Ant handled RMB118tr of payments ($17tr USD). This is a bit under 3x the total spending handled by Visa and Mastercard. It’s an astoundingly large number, not just because it exceeds China’s $14tr GDP. (Peer-to-peer transfers, loan borrowings and payments, or transfers from a savings account to a money-market fund would not be accretive to GDP but would show up in Ant’s total payment value number.)

But the payments business is not as exciting as it looks. In 2019, Ant reported total payment value of RMB111tr, and total payments revenue of RMB52bn, for a take rate of 0.05%. As Marc Rubinstein points out, even that exaggerates the economics, since Ant pays most of its payment revenue back to financial partners. After those fees, Ant’s share of payment volume is a bit over 0.01%.

Ant makes its real money from other financial services. In the last six months, payments were 36% of revenue, while expediting small business and consumer loans was 39%, investment products were 16%, and insurance was 8%.

In these businesses, as in payments, Ant mostly operates as an intermediary, connecting borrowers or investors to companies that can work with them. Ant’s ubiquitous payment product gives them a low cost of customer acquisition, and growth in China’s consumer spending is a tailwind.

Ant as a bet on consumer finance. In the US, it’s very easy to borrow money for consumption, but fairly hard to borrow to start a business. China’s financial system is geared towards financing things like steel mills and property developments, not providing consumers with revolving credit.

And this means that the upside case for Ant is that China’s economy gets more normal and balanced over time. China has had a heavily investment-driven model for decades: when growth is strong, companies invest their profits in more manufacturing capacity, and when growth is weak, the government builds more roads, ports, and power plants to keep GDP growth elevated. This model was effective when China was significantly underinvested—at the start of their industrialization, not only did China have few factories, but the factories they did have were often located in deliberately hard-to-reach places, to make the country harder to invade. This made last-mile transportation painfully expensive, so China’s industrialization in effect started from zero.

A small, poor country can afford to be dependent on exports, because their cost advantage means they’re somewhat insulated from drops in global demand. As a country gets richer, it runs into a problem: its own GDP is dependent on policy decisions made elsewhere. Refocusing on internal demand can give a country more policy flexibility, which is especially important as China’s exports get more politically risky. There are signs that this is already happening. Ant customers' outstanding credit balances compounded at 76% from 2017 to 2019. And debt collectors are growing, too.

If the upside case for Ant is that China gets more normal, the downside case is that things don’t change. One risk factor in Ant’s prospectus is the solvency of the banks and financial institutions they deal with. Assuming banks are solvent (or will get bailed out) is generally the default in rich countries, but it’s a meaningful risk factor in China because their banks' solvency is unknown, and banks have the implicit liability of needing to direct funds to projects that fulfill policy goals even if they’re not creditworthy.

Ant’s own background showcases the sometimes rickety regulatory framework in which Chinese companies operate. Ant’s predecessor, Alipay, was created as part of Alibaba, but in 2011 Alibaba quietly announced that it had sold Alipay to its CEO. At the time, some analysts speculated that Alipay was worth $1bn, but it sold for $51m, in two transactions in 2009 and 2010. This is not exactly stellar corporate governance (imagine Apple releasing an annual report where a footnote reveals that they sold the App Store to Tim Cook).

Alibaba’s explanation was that the Chinese government had created new rules around payments, which precluded payments companies from having outside investors. Those regulations do, in fact, make sense; China always runs the risk of money fleeing the country, and when money does so, it uses whatever the simplest channel is. The sale, at a low price and without disclosure until a year after the fact, was deeply concerning to outside investors, who demanded their money back. After extensive negotiations, Alibaba ended up entitled to 37.5% of Ant’s pretax profit, since converted into a 33% equity stake ($, FT).

This kind of deal has gotten rarer, but the risk doesn’t go to zero, and outside investors don’t really have recourse. In finance, there’s sometimes a phase change where a transaction goes from an iterated game to a one-shot game. For example, VCs tend to back founders because they don’t want to risk dealflow, but when one company is a large enough share of their fund (as Uber was for Benchmark), it makes economic sense for them to optimize for that one situation rather than future transactions. (An even easier call if you’re planning to retire after). In Ant’s case, investors have to hope that behavior improves when the game switches from iterated to one-shot. The optimal choice for Alibaba would have been to treat investors nicely when Ant was worth $1bn, and then exploit them more at a $200bn valuation.

Financial markets work well when property rights are certain, and easy to analyze. A complex financial system often involves borrowing against financial assets which are themselves secured by real assets or future incomes; that pyramiding of debt quickly falls apart if uncertainty about collecting it compounds through a complicated financial structure. Ant is a bet on this kind of certainty, in the face of a much stronger incentive to exploit uncertainty for the benefit of insiders.

[1] One reason for this is the pure volume of work. Chinese Internet companies often adhere to a “9-9-6” schedule—9am to 9pm, six days a week. A while ago, an anonymous whistleblower shamed some companies for this schedule and praised others for demanding less ($, NYT), but the companies on the praiseworthy list include Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, which have had difficulty making inroads into the Chinese market. Meanwhile, the worst offenders are Alibaba, JD.com, Huawei, and Bytedance. That list doubles as a short list of the most successful technology companies in China.

Elsewhere

The Startup Cycle

Silicon Valley famously benefits from a cycle where successful founders decide they don’t want to run a company any more, but still want to be involved in the business, so they start cutting checks and offering advice to new startups. Something similar is happening in electronics assembly in China: Lens Technology and Luxshare, two acquisitive contract manufacturers, were founded by former factory workers, one of whom got her start at Foxconn. In this case, there’s a commoditization angle, too:

Media reports from Taiwan and Japan saw Apple’s hand in the takeover too, claiming that the Californian giant is trying to groom Luxshare as a rival assembler of iPhones to Foxconn.

Buybacks

In the last few years, one theory of US equity outperformance was that it was driven by buybacks. American companies tended to return over 100% of their cash flow to investors, mostly in the form of buybacks, and all those share purchases would tend to bias stocks upwards. Spring 2020 was not exactly a test of this proposition, except in a limited sense: unprecedented monetary interventions from central banks with effectively unlimited buying power can, indeed, be a substitute for equity demand on the part of CFOs. In the coming months we’ll see a return to normal, as more companies resume their buybacks. Since banks have record deposits, often from corporate customers ($, WSJ), and are understandably nervous about reinvesting in their businesses, buybacks may quickly return to being the default option.

Return-on-Kickback

A new study ($, The Economist) shows that bribery has high expected returns: $6-$9 in market value per dollar paid, ignoring the risk of getting caught. The US has had a number of bribery scandals, in part because the US has a large economy with many multinationals and in part because America is relatively aggressive about enforcement (for comparison, Germany got rid of their tax deduction for bribe costs in 1998). As American regulators increasingly use the dollar system as a tool for enforcing rules, American bribery standards could become more universal.

Legalization

2020 is an interesting year for cannabis legalization. Congress is currently considering a bill, which may pass in the House but which likely won’t make it through the Senate. But there are two other reasons to expect it:

- States are desperate for tax revenue, and legal marijuana is naturally taxed at a higher rate than the illegal kind.

- Donald Trump has talked up criminal justice reform, and is running against a team of drug warriors. An October announcement that the Federal government will lighten up on cannabis-related enforcement would be a suitably Trumpian way to reframe the debate. It doesn’t exactly fire up Trump’s base, but Trump has always had more of a talent for giving people a reason not to vote for his opponents than convincing swing voters to support him.

Housing

After the financial crisis, Blackstone permanently changed the housing market by turning single-family homes into an investable asset class. This, I’ve argued before, permanently reduced swings in housing prices by creating a source of demand for homes that wasn’t fueled by selling other homes. They’re back in the market, with a new investment in a single-family rental company.

Meanwhile, one category of housing that’s doing especially well: vacation homes.

Big Tech, Monopolies, and Attack Surface

Software businesses lead to natural monopolies across a thin-but-wide slice of the value chain: dominating search, but not controlling the content; dominating social, but not owning news; selling game engines, but having a low market share in games themselves. This tendency means that an economy more driven by software will have more monopolies, but also that they will be more fragile. Three case studies:

- Facebook is testing linking news subscriptions to Facebook accounts, so Facebook users see more stories from publications they subscribe to. For the publications, this is yet another example of the endless tradeoff between more revenue (for now) and less control (forever).

- Roku has more bargaining power, now that its userbase (43m) dwarfs that of any major cable operator. Cable had distribution power because building a network was capital- and regulation-intensive, so it wasn’t economical for competitors to duplicate it. Roku found a much cheaper way to get between content and the end consumer, and now they’re monetizing it.

- Apple has dropped Epic Games' account from the App Store. This exemplifies the “attack surface” downside to monopolistic economics. Apple has worried and irritated many other game publishers by retaliating against Epic. Meanwhile, Epic lost a channel for all of their games because of an attempt to capture better economics for just one of them.

TikTok

One dog that didn’t bark with respect to TikTok: if the technology is so dangerous to the US, why isn’t China worried that an American company will control it? Now, they are. China has added some AI technologies to its export control list ($, Nikkei), giving them the potential ability to block a TikTok sale. The TikTok deal continues to get more complicated: there’s the US-TikTok negotiation, the TikTok-acquirers one, and now an acquirer-US-China one. Microsoft’s increasingly sophisticated lobbying efforts ($, NYT) mean they’re likely still the top prospect.

(Disclosure: Long MSFT, but not because of any TikTok speculation.)

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart