We're very excited to introduce our beta test for Diff Jobs. We've spent the last three weeks talking to dozens of companies and candidates about what's working and what's not in the job search process, from both sides. And we see lots of opportunities to start making connections within the Diff network. As the newsletter grows, the value of reader-to-writer connections scales just about linearly, while the potential value of reader-to-reader connections grows at more like n log(n). Scroll to the end of this newsletter to see some of the roles we're recruiting for and find out how you can get in touch.

Your Life is (Almost) a Call Option

It’s a recurring Diff theme to apply financial language to human behaviour. Markets are laboratories for the study of human behaviour, and as such they provide a great arsenal of vocabulary for explaining the non-financial world. If you don’t make a living as a derivatives trader, believing that volatility is a positive force might be counterintuitive. From birth, volatility in asset or commodity prices is presented as cause for concern. This is sensible at a societal level: uncertainty is not a stable base to build common prosperity. But since Keynes, economists have recognised that applying societal standards at an individual level and visa versa, might not be applicable. Understanding how volatility can be a useful force at the individual level is a necessary component of nonlinear thinking.

Take an example of a call option with an expiration one year from now and a strike price of $10. If the stock the option references is at $5, and its annualized volatility is 50%, the option is worth about 13 cents. In other words, the option buyer is making a bet on a fairly remote outcome. If the price goes up, the option is, naturally, worth more. It’s also worth more in response to volatility. And, the further away from the exercise price it is, the more volatility dominates: imagine the stock trades at $2.50, or half the previously assumed price, but the annualized volatility doubles to 100%. The value of the option rises in that scenario, to 17 cents.1

There are many situations in life that map to this out-of-the-money option math. Consider anything in your life that 1) you’d like to have, 2) that you probably won’t get, but 3) that it’s not logically impossible for you to get—and whose outcome you can in some sense control. Most of the pathological examples are pretty bad risk-adjusted bets: winning the lottery, becoming a world-famous TikTok personality, winning a national election, etc. But there are some more realistic options—long-shot jobs and career changes, side projects that could become more-than-full-time projects, and decisions in your personal life.

It’s important to note upfront that this mapping is imperfect. The reason stock options give us such clean, formulaic theories is that financial contracts strip away everything qualitative. The market only works if shares and dollars are perfectly fungible with one another.2 That said, the options approach does give some directional guidance; it doesn’t tell you the answers, but it might tell you where to look—and, what’s particularly valuable in general frameworks for how to live your life, it’s especially useful for dealing with adversity.3

It’s common preparation for a job interview to run through hypothetical scenarios the interviewer might throw at you. “Why do you want to work at X?” and “How do you explain this 4-year career gap?” (extra points if you answer without using the phrase “misspent youth”). But a scenario you probably haven’t war-gamed: what do you do when you get knocked off your motorcycle on the way to the interview? If you’re Bob Chapman, and on the way to a Salomon Brothers interview, you keep going. He showed up covered in blood, and got the job.

The situation perfectly illustrates the dynamics of volatility. After the accident, your odds of getting the job are pretty low. If you show up to the interview and crash-and-burn (so to speak), you’ve got an easy excuse. On the other hand, you’re bound to stand out amongst the pool of applicants and nobody will question your commitment, so you might as well give it a try. In option terms, Chapman’s current price went way down—the visibly bleeding interviewee has worse odds than the one who shows up looking sharp. But the variance went way up! His interview was definitely going to be the most memorable one for that role, so all he really had to solve for was a) appearing generally qualified, and b) convincing his interviewer that the motorcycle-riding and accident demonstrated the right kind of risk tolerance.

It applies to corporate strategy, too, especially for desperate companies. The founders of Ozy also thought they might as well pursue a high-variance/low-expected value strategy. The digital media startup was trying to raise $40 million from Goldman Sachs’ asset management division. As Money Stuff covered this week, the founders of the digital media startup impersonated a YouTube executive to deceive Goldman’s due diligence before the investment. Clearly, the founders felt they were out-of-the-money if they didn’t take action and to their mind, the downside of being discovered was having to fundraise elsewhere. On the flip side, they would receive their funding and Goldman would be incentivized not to disclose that Ozy had tricked them. By anyone’s determination, this strategy increased volatility.

However, Ozy hadn’t factored in Goldman going to the press, once they discovered their conversation with Samir Rao, Ozy co-founder, was not with Alex Piper, Head of Programming for YouTube Originals. This is a great illustration of why purely option-driven thinking is a guideline but not an absolute. As it turns out, Ozy did not have a pure out-of-the-money option, with no downside from increasing volatility. Instead, they had serious downside risk, which continues to play out.

The optionality approach is morally neutral itself, but often recommends morally dubious behavior. Committing crimes or engaging in deceptive behavior generally is certainly a way to raise the variance in your outcomes! But it might make sense to treat this as a backwards-looking explanation rather than strict guidance: the reason we should find it unsurprising that some companies commit blatant deceptions, like faking a meeting with an executive, is that they have little to lose. (In this case, the little-to-lose may come from earlier deceptions; Ozy has cited a 25 million member newsletter, but its public presence doesn’t really match this. For example, the company’s Twitter feed allegedly has 45,000 followers, and its most recent tweet has, in the seven hours it’s been up, gotten zero likes, zero retweets, and one response—about the scandal, not the story the Twitter account shared.)

It’s possible to imagine an Ozy model where exaggerated engagement got them funding, and that funding allowed them to pay for content that would then produce engagement numbers in line with what they’d originally promised. There are many strategies for building a big media and influential media company, and one approach is to act as if it’s already built and use that impression to raise the funds and attract the talent necessary to make that come true. (If we think of media companies as being in the business of shaping public perception, you should be suspicious of any media company that doesn’t give the world an exaggerated sense of that company’s own importance. Are they really good at their jobs!?)

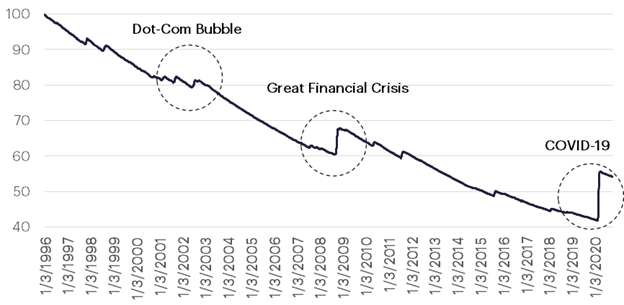

But it raises another important point about optionality: historically, people who blindly buy stock options lose money over time. Verdad Research has a wonderful new post about this, with a pretty damning chart that goes almost straight down with only the occasional jump during times of market chaos.

Normally, producing gains of around 13% during a financial collapse would make you feel very smart indeed, but for the blind put option buyer, it’s quite depressing; it’s a reminder that when their strategy really pays off, that means going from down 40% to down 32% since inception.

But that’s a result of a market where there’s a wide range of assets quoted, and there’s always someone on the other side of the trade. If you’re given a set of options with market prices, and you insist on constantly buying those options, you’ll tend to underperform over time. But in the real world, the option-like situations you’re presented with are somewhat random; it’s not an opportunity available to everyone in the world with a brokerage account, but an opportunity available to a more select group of people. And the pricing and payoff of those option-like opportunities isn’t subject to the market’s imperfect but relentless pursuit of maximum efficiency.

There’s another side to the options trading dynamic, and it also has some explanatory power: in high-prestige, highly-tracked careers—Biglaw, Big Three Consulting, increasingly Big Tech—the winners are a) generally people who are well-qualified for what they got, but also b) people who lucked out in a process that has an element of randomness. It’s intuitive that if a group of people are being assessed in roughly the same way, stack-ranked, and then allowed to advance only if they hit a certain cutoff, there will be some mix of luck and skill in the outcomes. But what’s perhaps less obvious is that the more people who are competing, and the more fine-grained the assessment is, the more the outcome depends on luck versus skill. Trying to figure out if someone is 95th percentile or 50th percentile is doable in many domains, but if you’re trying to select for 99.5th percentile, what you’re effectively doing is picking out people who were near the top and also happened to be lucky in some way.4

This tends to make the winners of such a contest risk-averse; within their cohort, they see that past success is partly random, so they know that future variance is more likely to make them worse-off than better-off. And since the people who succeed in these careers have substantial real-world influence, that means there’s a growing tendency to bet against volatility rather than betting on it.

Which adds yet another way that the market metaphor is imperfect but action-guiding: stock options are expensive because the number of people who think something exciting will happen imminently is higher than the number of people who wake up ready to explicitly bet that the future will be boring. But in careers, the opposite dynamic may hold: there are many career paths that encourage winners to bet against volatility, which means there are lots of opportunities to take the other side of the trade.

A word from our Sponsors

Managing bills shouldn’t require sacrificing your investments. With M1 you can borrow against your investment portfolio to pay the bills and keep your money in the markets.

M1 is the all-in-one Finance Super App that allows you to invest, borrow, and spend your way, and M1 is fully integrated to make your money movements smoother and your financial life easier. Plus, it's free to download and get started. M1 is for savvy investors, like readers of The Diff, who want to take control of their finances and commit to a long term strategy.

M1 is not for day trading. It automates away day-to-day interactions so you can concentrate on the bigger picture. You can follow curated portfolios, schedule investments, automatically reinvest dividends, and rebalance your portfolio in just a few taps.

M1 is the Finance Super App: easy to use, award winning, and Yours to Build.

Investing in securities involves risks, including the risk of loss. Borrowing on margin can add to these risks. M1 Finance LLC, Member FINRA/SIPC.

Elsewhere

Reactive Strategy

The Information has a great profile of the head of Amazon's ad unit ($). One interesting detail is that Amazon's ad product, now a lucrative revenue source, was originally more defensive:

In the mid-2000s, Amazon developed an internal “Google reliance” metric, which focused on how much Amazon itself was paying Google to bring shoppers to the retailer’s site through search ads. If that metric remained high, executives worried, Amazon could be in jeopardy if Google itself ever decided to make a more serious foray into online commerce.

Amazon’s solution was to convince shoppers to start their product searches on Amazon rather than on Google, by investing in the retailer’s own search experience...

As it turns out, one of the better ways to avoid being reliant on one company is to carefully recreate enough of its features that you can recreate some of its business model, too; you can look at Amazon's ad product as fundamentally a search business, and can treat the rest of the company's e-commerce activities as efforts to drive more lucrative search traffic. Selling ads in search results is one of the best business models in existence. Having to actually build the product listings pages, store the products, and ship them makes it less scalable, but those costs actually make it much more defensible. Amazon built a sufficient subset of Google for its own purposes, and it would be murderously expensive for Google to build a meaningful subset of Amazon to fight back.

(Disclosure: I own shares of AMZN.)

Working it Out

The situation with China Evergrande remains both well-covered and uncertain, but we can get some interesting indications of where it might go by looking at similar cases. HNA is not directly comparable, since it was a global conglomerate that snapped up trophy assets mostly in travel and finance, rather than a local company in the real estate market, but it did have a sudden collapse, and is now being worked out. The company has announced that it has a total of $170bn in liabilities ($, Nikkei). And the number's source is also interesting:

Gu Gang, head of HNA's court-appointed working group and secretary of the debt-laden conglomerate's most important Communist Party cell, reported to almost 2,000 party cadres and employees of subsidiaries in an internal meeting

Once a company in China gets into big trouble, it's the Party's business. For a deeply indebted firm, that's actually good for their prospects of gradual liquidation—state-run or state-influenced banks can help them restructure without a fire sale. And that's especially important because of how big housing is as a share of China's GDP and of household net worth ($, Economist). It's easier to restructure one big company's debts than to restructure those of hundreds of millions of households, and bubbles can be sustained for a long time given enough liquidity. So that points to the approximate shape of Evergrande's ending: the company will be restructured, and China's policy will be geared around keeping housing prices roughly flat so the economy can grow to a point that those housing prices are justified.

Standardizing the Metaverse

Epic Games is offering its child safety services to developers for free. If the metaverse ends up being a series of interoperable game worlds, where the same avatar can be used to socialize with friends, watch a movie with them, and shoot them in Fortnite, then participants will need similar standards because the lowest standard of any one member of the platform determines the baseline for everyone else. The alternative is a less interoperable metaverse, but that's not good for Epic: since Fortnite is so big, and has tested out so many non-gaming experiences already, any standard that it follows becomes the de facto standard, and that means more metaverse users end up using Epic's platform rather than someone else's.

Probability

Amazon is giving some workers free cars and $100k prizes in a vaccination lottery. One theory is that a driver of vaccine hesitancy is scope-insensitivity around low-probability, but very bad, outcomes. Amazon is buying into it, and is basically giving scope-insensitive workers an opportunity to apply the same bias in the opposite direction; winning $100k may be unlikely, but if sufficiently low numbers round up to incommensurable "maybes," then it's a strong motivation.

When Payments Work

Part of the original thesis for Paypal was that people who lived in unstable countries prone to high inflation would want somewhere to store their cash where the local printing press couldn't affect it. This turned out to be a less pressing opportunity than lubricating the Beanie Baby Bubble—as it turns out, American toy collectors have more disposable income than people in third-world countries—but the idea has worked out: hyperinflationary Venezuela now has widespread adoption of digital payments. This is partly driven by the ability to swap into other currencies, but also by the ability to quickly settle transactions and then spend the money elsewhere. When inflation is running at 2,500%, getting paid in a week means accepting a 14% discount. Ironically, using technology to raise the velocity of money makes inflation worse in the short term, but it also equips people to care about it a bit less.

Introducing Diff Jobs

The Diff is pleased to announce the beginning of our job matching beta test. We've talked to dozens of companies about open roles, big problems, and interesting opportunities, and we've also talked to readers about what they're looking for, what's hard to find, and how they evaluate teams. Some interesting open roles:

- Rapidly scaling climate tech company is looking for a capital markets lead who can help finance ambitious climate solutions.

- Fintech startup is looking for a strategist who can articulate systematic investment strategies to everyday investors.

- Life sciences company that's applying a new and aggressive model to research is looking for an in-house PM who can help researchers accelerate their work.

- Fintech startup that helps platforms offer innovative financial services to their sellers is looking for multiple roles, including a Head of Capital Markets.

- We're working with several exciting projects in the Web3/DeFi/Blockchain space, especially for people who are able to operate at the intersection of a technical understanding of protocols and the ability to work with users.

- … and more.

If you're interested in applying, please reach out with the form below: we'll contact you, talk through your background, and see where we can find a fit. We won’t share your information with anyone else without your permission. (If we don't find something right away, don't worry—we're onboarding many new companies right now, and some of the companies we've talked to have hiring needs further in the future.)

This dynamic hurts people in the opposite direction, when they use put options to make bets against stocks that are volatile because they’re in the middle of a short squeeze. For reasons that we won’t get into—because they only matter to options traders, for whom they’re pretty self-evident—using options to bet against stocks that are expensive or impossible to borrow is basically a way to use the options market-maker’s balance sheet instead of your own. The problems with this are twofold: first, it means that options prices actually reflect this demand for stocks that can’t be borrowed at big retail brokerages. Second, in short squeezes the underlying volatility seems to peak when the stock is going up, and then decline as the stock drops .

For example, Gamestop’s annualized volatility was over 600% in late January and early February, when the stock hit $400. By May, with shares in the mid-100s, annualized volatility had dropped to 100%. Someone who bet against Gamestop at the peak could, depending on what they owned and when, have lost more money on the decline in volatility than they made on the decline in the stock price. ↩

And even then, we’re cheating a bit by treating Black-Scholes as a perfect indication of what an option is worth. In practice, there are other considerations driven by both real-world concerns and market structure. (On the real-world side: a biotech company with a drug in stage-3 trials has a bimodal outcome, and options on it won’t be priced according to a normal distribution. On the market structure side: if you know that a big holder of a given stock has a margin loan, and will be forced to sell if the stock hits some price, your options model needs to take into account the “air pocket” in the market price. The advantage of using Black-Scholes is that it’s fairly simple, and since everyone agrees that it’s imperfect using it produces less debate than using a better model that relies on more debatable assumptions. ↩

There’s a hard-to-avoid pathology in the self-help space where people’s ability and willingness to improve their lives fluctuates, and often at the high point of a low period, they’ll decide to make some improvements. But they often revert to the norm soon after. So many life changes are implicitly designed for someone more functional and ready-to-fix-things than the person who will actually be implementing them. This applies much more to self-help concepts than to self-help services—in fact, the function of people in the self-help business, whether they’re therapists, consultants, coaches, or clergy, is to calibrate their advice so it’s the best thing the person they’re talking to is currently capable of doing. ↩

This is partly due to another curse of variance: the more extreme an outlier is, the harder it is to meaningfully compare them to someone else. You can measure whether someone learned basic calculus with a standardized test, but it’s hard to come up with a good test for the smaller subset of people who independently re-derive important discoveries on their own. There’s a wider range of possibilities to test for, and, even worse, if they invent something completely novel then a pre-arranged standardized test awards them precisely zero points even if they outperformed everyone else. There’s a wonderful fictional depiction of this in Cryptonomicon, in which a character gets a word problem—the boat is moving at 5 miles per hour, and the river is flowing at three miles per hour, someone drops a hat in the water, etc.—and starts deriving new corollaries to the Navier-Stokes equations instead of answering what’s meant to be an arithmetic question. ↩