Data's Limits and the Judgment Gap

It would be convenient, for the purpose of generalizing consistently, if we could put solid numbers on the share of successful organizations that are, or consider themselves to be, "data-driven." Sadly, there's a paucity of actual data here, but approximate indicators—the fact that few will admit to not being "data-driven," the prevalence of quantitative arguments for business decisions, and the roughly 200 Zettabytes of data the world will store by 2025 all indicate that it matters.

But high-functioning organizations can't make their most important decisions with data, because the more pivotal the choice is, the less data you'll have. Netflix knows just about everything about how marketing, recommendations, and thumbnails affect someone's odds of starting to watch something, and about how stars, story, and production values determine their odds of finishing. But to get to that point, they had to more or less invent the modern video streaming ecosystem.

A common way to model companies is to split them off between cash cows and growth businesses. The cash cows are easy to model, but that ease of modeling means that there's a limit to how much upside they can offer. The rest of the business gets treated as a portfolio of lottery tickets, with higher uncertainty for both their cost and their payoff. But you can also think of the company as having an information portfolio that lines up nicely with this: the core business is easy to model because the inputs are well-known, and even the uncertain parts ("How many DVDs of Avatar do we really need to order?") have a fairly predictable range. But the growth process can partly be modeled as a search for newer and better KPIs.

Think of the traditional media giants' transition to streaming. Disney knows all there is to know about repackaging IP in order to monetize it through movie tickets, cable carriage fees, ads, theme parks, cruise ships, toys, live appearances by Mickey and Minnie Mouse that happen to wipe out the catering budget at a wedding, etc. Disney knows a lot about these customers' price sensitivity and brand affinity at a high level, but there's a lot they don't know but would like to about the granular details. A particular character might be wildly popular with the biggest fans, as demonstrated by action figure sales and the like, but not as interesting to the average customer, and thus not worth their own movie spinoff. A franchise might subtly be getting played out, but still be interesting to fans who reliably attend the Nth Marvel iteration because of the sunk cost of all the time they've already invested in it. Streaming offers more granular data: what do people watch, and what do they rewatch? When do they pause, and when do they give up? Do they navigate by category, or always look for one specific thing?

That information is all useful for making a streaming service better, but it's also useful for the entire intellectual property constellation—the data return for streaming services shows up in every other part of the business, too.

It's partly one more way to monetize IP, but it's really a way to get a much more detailed look at exactly what customers respond to. There's always an imperfect connection between what a project is and what its job to be done is, and finding new metrics to track is one way to close that gap.

Sometimes, companies' strategies look like they're a transformative plan but are actually a natural incremental adjustment. Consider Netflix's 2016 decision to launch in an additional 130 countries. At one level, this was a sweeping change from their previous approach of opening up one or a handful of markets at a time. Before this, Netflix laid more groundwork, acquired local content, and set up a marketing blitz, but in this instance they just flipped the switch and made their product ubiquitous.

But Netflix wasn't really launching "globally": in effect, they'd identified a sort of distributed country with outposts in every major city, consisting of well-educated high earners who think in US Dollar terms, have US credit cards, pay for broadband connections, and speak English. This country doesn't exist on a map, though if you draw a half-mile circle around every place where you can redeem Marriott Bonvoy or Hilton Honors Points you get close. And while it's not as big as other countries they launched in, it is rich.

And Netflix had done a sort of soft launch already, in the sense that people outside its core markets sometimes used VPNs to access the product. While Netflix couldn't necessarily track the origin country for those users well, it could infer usage based on local traffic to its sites, or by looking at publicly available Google Trends data. And conveniently for them, launching in a distributed nation of people plugged into the English-speaking, credit card-using world had the spillover benefit of making their product available to everyone else in those countries, which gave them enough incremental usage data to know where to concentrate their efforts next.

So that move was more data-driven than it appeared to be and a way to spin up even more data.

Contrast that with the plan to launch an ad-supported tier. Netflix has historically had a category of less-monetized users—the ones on free trials. For them, the service basically is an ad, and the upside comes entirely from conversions. Launching an ad-supported tier forces Netflix to deal with many more unknowns:

- How much will this cannibalize current paying subscribers?

- How much will it cannibalize future paying subscribers, especially if the price increases?

- Will this weaken their status as an easy default? Netflix tries to be the last decision users make before deciding to sleep; will that habit be weakened with ad breaks?

- Will this hurt their ability to win over content creators? Paid media has more cachet than ad-supported media, and it's easier to go downscale than upscale.

In the short term, these are incredibly hard to calibrate. It's easy to imagine the ad service being a disaster in either direction: the company might delay other projects, put stress on its systems, deal with employee churn—and end up with a few million incremental users who don't monetize nearly as well as the core business, and aren't numerous enough to get economies of scale in the ad business. Or, even worse, they could end up with an ad-supported service with tens of millions of users, many of whom are former subscribers to the paid service and who would have continued using it if it had been the only option.

Upfront, there are too many unknowns to get this right. But over time, what Netflix ends up getting from an ad-based service is a more detailed demand curve at a customer and country level. That demand curve will smooth out the returns from newly-acquired content and give them more data around the impact of pricing changes or further restrictions on account sharing.

And it helps in another way, too. If ad-supported users are less engaged, they also burn through content at a slower pace. Some media companies go through a phase where most of the value is in their back catalog of content, not the future additions.1 Netflix is a long way from that point, but if they ended up with a large base of fairly passive users who treated them as a backup entertainment option and weren't too upset by interruptions from ads, it would mean that the content asset on their balance sheet would be accumulating economic value in addition to accounting value.

It's harder to run a business with more moving parts, but if creating such a business also throws off more data, it can be a way to fight entropy. Every incremental way to sell the same thing will add complexity to the model, but it also adds some customers who weren't available before, and clarifies exactly where existing customers are making their marginal decisions.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Here's a dirty secret: part of equity research consists of being one of the world's best-paid data-entry professionals. It's a pain—and a rite of passage—to build a financial model by painstakingly transcribing information from 10-Qs, 10-Ks, presentations, and transcripts. Or, at least, it was: Daloopa uses machine learning and human validation to automatically parse financial statements and other disclosures, creating a continuously-updated, detailed, and accurate model.

If you've ever fired up Excel at 8pm and realized you'll be doing ctrl-c alt-tab alt-e-es-v until well past midnight, you owe it to yourself to check this out.

Elsewhere

Mobility

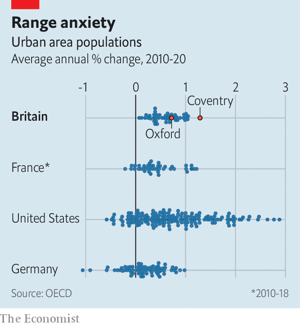

This Economist piece highlights how almost all British cities grow their populations between 0% and 1% annually ($), with minimal variation. Other countries have more variance, with both the US and Germany showing some cities shrinking while others grow, and the US in particular with some extreme outliers.

One paradox of housing availability is that in the short term, restricting housing availability and letting prices fluctuate makes cities more specialized and more productive: if tech prices people out of San Francisco and finance prices them out of New York, then those cities get a denser network in the industry they specialize in. But in the long term, it's self-defeating even for the narrow purpose of raising a city's per-capita economic output: the people who get priced out are not just the ones who aren't working in the key industry, but the ones doing something risky that doesn't pay well just yet (both Airbnb and the prime brokerage industry were partly the result of temporary real estate gluts, and both would have been harder to create if prices had been higher2). And second, some industries scale for a long, long time, and end up tapping out local labor markets entirely. If they're capacity-constrained because the city they're in won't build, they'll eventually relocate to somewhere else.

More Housing, Just in Time

Housing observer Bill McBride estimates that housing completions this year will probably reach their highest level since 2006, as homes started last year but delayed because of supply chain problems finally get finished. It's been a while since we've seen a surplus of housing (and a long-term chart of new home starts shows that the post-crisis shortfall was bigger than the pre-crisis overbuilding). But the housing market is very different from what it's looked like historically; compared to 2006, the marginal buyer has been much better-funded and has had a better credit rating, and there's much more institutional capital in the market. Rising rates make new homes less affordable, but the inflation that led to those rates has kept rentals an interesting asset class—they're a long-duration product, but one whose value is fairly insulated from inflation. And if there's a large cohort of workers who are earning more than they used to, but not enough to save for a downpayment yet, there's room for these companies to capture some of that spending power in the form of rent.

Wargamification

Smartphones' impact on war is most visible in analysis and propaganda—it's easier for compelling stories and videos to spread further and faster when sharing is easy, and that creates an incentive to craft narratives carefully. But smartphones are a two-way medium. This piece ($, Economist) is mostly about the impact of artillery on the war in Ukraine, but includes a notable detail:

Russia is now using group channels in messaging apps like Telegram to aim its artillery better. Russians pretending to be Ukrainians on these channels feign fear of shelling in order to elicit information about infrastructure that has and has not been hit. On May 24th the SBU revealed an even more devious approach to such espionage. The agency said it had discovered that Russian intelligence was using smartphone games to induce unwitting youngsters to snap and upload geotagged photos of critical infrastructure, military and civilian.

If most of the world's cameras that are being actively used by someone are in the hands of individual smartphone users, then the highest-leverage source of intelligence is to get a small fraction of them to point their cameras in strategically valuable ways and share the results.3

Worker Shortages

I mentioned the possibility last week ($) that a major driver of higher compensation for the bottom quartile of US workers was that Amazon had a) hired a lot of them, and b) set a de facto minimum wage for unskilled workers at $15 in 2018, with raises since then. A leaked memo from 2021 discusses the risk that the company might run out of workers by 2024.

The model of these workers as a depletable resource is an interesting one. The article cites annual turnover of 123% in 2019 and 159% in 2020, indicating that there's a large cohort of workers who try working at an Amazon warehouse, quit, and never come back. The company can expect some workers to stick around for a while, but mostly seems to need a continuous stream of new workers to keep replacing the ones who leave. This is probably part of why Amazon started offering to pay for workers' education: better for them to spend four or six years working at a warehouse and then quitting to do something with their degree than for workers to spend a few months at the warehouse and then leave to work at another low-wage job.

Disclosure: I am long AMZN.

Taiwan

The US, Europe, and China are all increasingly subsidizing domestic chip production in part to avoid dependence on Taiwan, but it's a moving target: there are 20 Taiwanese fabs, worth a collective $120bn, either new or in the pipeline right now ($, Nikkei). Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.'s latest product roadmap has also just been released, and while the pace of new nodes is slower, they're still driving improvements, especially in power consumption. Since TSMC dominates the leading edge, the fact that they've slightly slowed down their pace of launches could be seen as evidence that there's room to catch up; they need to be the best, but not necessarily by a huge margin. But since they're well aware of how competitive the chip industry is, a better conclusion is that even the best companies in the industry are finding incremental improvements harder and harder to deliver.

Diff Jobs

Diff Jobs is our service matching readers to job opportunities in the Diff network. We work with a range of companies, mostly venture-funded, with an emphasis on software and fintech but with breadth beyond that.

If you're interested in pursuing a role, please reach out—if there's a potential match, we start with an introductory call to see if we have a good fit, and then a more in-depth discussion of what you've worked on. (Depending on the role, this can focus on work or side projects.) Diff Jobs is free for job applicants.

- The Diff is looking for an associate to support with Diff Jobs, newsletter growth, research, and other areas of the business. (Remote, Austin a plus)

- A company building an artificial intelligence tool to support the early stage investment process is looking for ML researchers with an interest in finance, or quant devs with an interest in software engineering. (SF or US, remote)

- A company building at the intersection of the traditional insurance industry and crypto is looking for a Chief Insurance Officer. (US, remote)

- A company helping financial institutions, exchanges, and governments to prevent financial crime on blockchains is looking for people from a data science background. (US, remote)

- A company which is helping brands use web3 to better engage and retain customers is looking for a senior engineering leader. Web3 experience not required. (US, remote)

- Companies in fintech and edtech are looking for data engineers with a variety of experience required. (various locations)

Disney is particularly hard to measure here, since it depends on whether you count stories and characters or actual movies. There are layers of unpredictable fixed costs for long-lived assets and more predictable incremental ones for short-term assets: the marginal cost of one VHS tape or DVD was low, and its revenue was quite predictable; there's a sense in which building a fictional universe is an unpredictable multi-billion dollar investment that takes a decade or more to pan out, while producing one more Marvel or Star Wars movie is a comparatively predictable and scalable effort. ↩

The Airbnb story is well-known, and the prime brokerage story is harder to find—if you know of a good history there, please reply and let me know! What is true is that there are anecdotes about brokers letting a client temporarily borrow a) office space, and b) their balance sheet, in exchange for commissions. ↩

This is yet another instance of a trend that was broadly foreseen in science fiction and later turned out to be real. Charles Stross' Halting State, published in 2007, deals with, among other things, the use of online games for intelligence gathering. ↩

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart