Public policy is a powerful tool, but the two things policy can’t beat are technology and demographics. We’re used to thinking about technology, because the benefits are distributed according to whoever understands it best. Demographics are different: the edge from understanding them isn’t big, except perhaps for market-timers. Certainly, fast food restaurateurs made money in the 50s and 60s taking advantage of the bulging teen labor force, but it’s unlikely that they planned it that way. On the flip side, when dependency ratios go down (i.e. there are more retirees per worker — which is happening in every developed country over the next century), it means redistribution away from workers. Policy gives you a menu of options, from left redistribution via pension and welfare or right-redistribution via 401ks and reverse mortgages, but either way, the population of non-working spenders will rise.

While you mostly can’t benefit from understanding macro demographic trends as an individual, you can benefit from figuring out the micro trends. There’s a phenomenon that’s happened across several industries, most visible to me in finance (because I read a lot of financial history), but anecdotally repeated elsewhere. The Long Generation: when a field peaks in popularity and declines, it starts to age rapidly, which affects how risk-sensitive practitioners are, and this causes a feedback loop: more risk-averse people are less inclined to shake things up, so stagnant fields stay stagnant. Then, either because of the vicissitudes of fashion or because of the raw demographic power of people retiring and/or dying, young people show up and a bubble commences.

As a stylized model, here’s the lifecycle of a career in terms of income and asset accumulation:

- 20s: low income, net negative financial asset accumulation; net positive asset accumulation, but mostly in the form of intangibles (skills and social capital). It’s best for young people to optimize for social capital over financial capital, just because it’s the path of least resistance. You can “own” something in the business-process sense (“she owns that product launch deadline”) well before you own equity.

- 30s: higher income, net flat to positive financial asset accumulation, slowing skill accumulation, accelerating social capital accumulation.

- 40s-60s: here’s where people reach career cruising altitude, and transform their social capital (the people who trust them) into income and balance sheet capital. Sometimes this happens in a very direct way; the standard path for VC partnership seems to be a senior operating role at a startup, so even if you don’t end up with much equity when it exits, your next job has carry.

Industries with an older average age have more financial and reputational capital to deploy, so the implied cost of capital to new entrants is lower. Conversely, if you’re in an industry that’s expanded a lot recently, such that there’s a huge cohort of people just out of college, there’s fierce competition for having enough responsibility to make an impact. And just like in financial bubbles, when everyone is competing for opportunities, the only way to get one is to accept a suboptimal investment. In other words, you can always find something to be responsible for, but it’s going to be in the sense of “Who is responsible for this disaster?”

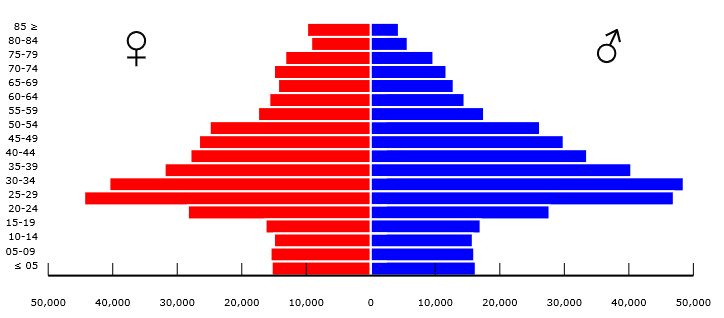

Because switching careers is hard, different industries have different demographic pyramids: a bulge when the industry was hot, a squeeze when it wasn’t. And for many successful people, good timing consists of getting in before one of those bulges happens.

Post-1929: Finance’s Lopsided Demographic Pyramid

My favorite example of this is the career of Warren Buffett, since it so perfectly captures the generational aspect. Buffett was born in August of 1930, less than a year after the crash. In the 1930s and 1940s, basically nobody went into finance. There wasn’t any money in it, and anyway, there weren’t any job openings. There wasn’t anything to do — there are stories about NYSE floor traders in the 30s having paper airplane contests while waiting to handle the occasional sell order.

Stocks hit a low in 1932, but trading volumes were still far below their 1920s height. When Buffett went to work for his father’s brokerage in 1951, it wasn’t just a contrarian move — it was dated. The 2018 equivalent would be something like moving to Seattle to start a grunge band. The world had moved on.

Think about the median professional investor circa 1951. It’s been 22 years since the crash, so he’s at least forty. (And if he joined the industry right near the peak, he was more likely to churn out — no time to accumulate financial or social capital before everything falls apart.) So really, more like fifty. The most memorable part of his career is still 1929, or the various subsequent panics. So what he knows is that:

- Growth stocks are prone to bubbles.

- Economic prosperity also leads to bubbles.

- When things get bad, stocks can trade at well below any reasonable assessment of their intrinsic value; if a company trades at less than its net cash on hand, there is no cosmic law stating that, a month from now, it can’t be trading at half of net cash.

So, this median money manager is skeptical. He feels good about high-grade bonds, okay about blue-chip stocks, and skeptical of anything that reminds him of the 20s. (And with the Dow finally staying about 200, on its way to 300, every milestone is the highest-since-the-bad-old-days, so every record high makes him more nervous.)

Buffett would have done well in any era, but the reason his early career was so extraordinarily great was that his competitors were all just trying to make it to retirement without losing it all in another crash. This gave Buffett the opportunity to clean up on buying undervalued stocks, and to hedge his market risk by shorting blue chips. Over the course of the 1950s, a few more oddballs made it into the industry. Gerald Tsai (born: 1929; started his career: 1951) was a notable example. Unlike Buffett, he focused on technology stocks. But much like Buffett, he had a demographically-driven near-monopoly: to most of his competitors, investing in cutting-edge companies meant losing your shirt on RCA or an over-levered electrical utility; when Xerox and Polaroid and the many varieties of -tron and -onics firms showed up, they stayed out.

And this created its own distortions. Purely due to the vagaries of demographics, the first generation to re-enter finance since the Depression focused an inordinate share of their attention on technology. And because they didn’t remember 1929, they were willing to take greater risks — risk appetite plus a bull market equals outperformance.

We all know that whenever young people are making money doing something old people don’t understand, the financial media will be all over it, ready to declare them geniuses. This happened in the 60s, the first era of the celebrity mutual fund manager. In addition to Tsai, there were several Freds (Mates, Carr, Alger), who all made money in small stocks, growth stocks, and small growth stocks. But market distortions tend to disappear far faster than they’re created; it took two decades for the market to become entrenched in its low-risk blue-chip preferences, and only about a decade for growth investing to lead to a massive late-60s bubble, which collapsed painfully. Some of the 60s stars left behind solid institutions; some of them left behind flaming wreckage. Since Buffett got in a little early and got out with exquisite timing, the 60s demographic bulge of small-stock fans gave him plenty of people to sell to when he liquidated his hedge fund.

It would be hard to match Buffett’s timing; he was lucky and smart. But other people have pulled off similar performances.

More Case Studies

It’s happened elsewhere: a while ago I read an interview with a hedge fund manager who covered energy stocks in the late 90s. His wife covered Internet. Oil company conferences in 1999 had attendees in their 50s, cheap food, and the giveaway goodie was a company decal. Internet conferences were full of Armani-clad 25-year-olds eating sushi; the giveaway was a Palm Pilot. We know in retrospect that 1999 was a great time to be an energy investor with an appetite for risk, and over the next two decades those energy investors got plenty of sushi and Armani themselves.

And here’s Marc Andreessen:

I just went to college. I did my thing. I came out here in ’94, and Silicon Valley was in hibernation. In high school, I actually thought I was going to have to learn Japanese to work in technology. My big feeling was I just missed it, I missed the whole thing. It had happened in the ’80s, and I got here too late.

You can also see this in politics today today: if you were an immigration restrictionist free-trade skeptic in the 90s or early 2000s, you’d probably conclude that you should spend your life on something other than trying to get Republicans to listen to what you had to say. There were some survivors, but they were survivors, operators like Bannon and Stone, who seemed to take perverse satisfaction in the unpopularity of their views. So the Trump administration is also demographically lopsided; lost in all the noise about the many surprising aspects of the Trump administration is the fact that some of the major players (Sarah Huckabee Sanders, Stephen Miller) are in their early 30s.

In media, my favorite case study is Cheddar versus CNBC. CNBC has locked down the demo of people who had money in the market in 2008; Cheddar is speaking almost exclusively to an audience that didn’t. The messages are so different that there’s no point in having one product targeting both audiences.

It’s probably happening now in media and finance. The people who got in will stay in, but the days of endless headcount growth are likely behind us for both. Which means that there will be a demographic bulge: the people who got into finance in the mid-2000s and who got into digital media in the mid-2010s will be the largest demographic in those industries ten or twenty years from now, too, which will reshape things towards more risk aversion.

(In finance, we’re seeing the aftereffects of a different demographic swing: as retail investors shift from individual stocks to indexing, the scope for micro-inefficiency — individually over- or under-valued stocks — diminishes, while the scope for macro inefficiency — over- or under-valued asset classes — increases. And one difference between micro- and macro-inefficiency is that betting against macro inefficiency has negative carry.)

The Test

If it were easy to differentiate between a secular decline and a long cycle, we’d live in a different world. But it’s not: there is no good a priori way to distinguish between an industry that’s temporarily out of fashion and one that’s in terminal decline. But demographics can help. Turn back to the oil example, or finance in the 50s: the industry had stabilized; people were leaving as they retired, and not many people were joining, but it didn’t seem to be getting any worse. And if an industry stabilizes, there’s probably something there.

It’s hard to scout out opportunities like this: you can’t exactly make a list of all the companies that didn’t recruit on campus this year but will be recruiting hard five years from now.

If you’re thinking ahead to the rest of your career and your competitors are only thinking about the next five years before retirement, you have an advantage. And you can use a couple heuristics:

- Browse business books on Amazon, and look for stuff published ten years ago that’s priced at $0.01/copy plus shipping.

- Look up companies in that industry on LinkedIn, and see if anyone working in the field finished college in the the last ten years.

- Somehow figure out what parts of their business are automatable. Companies that have been through a bubble/bust cycle are risk-averse, but if you find a way to save them labor when they’re slowly losing headcount through retirement, you’re in a good position.

This turns macroeconomic bad news into personal good news. I happen to be kind of worried by the fact that outside of a few sectors, the US appears to be getting less productive and less competitive over time. I’m especially worried now that around ten thousand Baby Boomers are retiring every day. That’s ten thousand people quitting their jobs, swapping their retirement accounts from equities to bonds, but continuing to consume (retirees consume about two thirds what they consumed when they were working, but the boomers have accumulated lots of capital relative to younger generations, so the wealth effect may keep them consuming more — which means the dependency ratio understates how much consumption workers will have to give up).

That’s bad news, and a government subject to two-, four-, and six-year elections is, naturally, completely oblivious to this generational cycle.

But at least somebody will get rich from it.