Instacart is the Best and Worst Grocery Business Imaginable

Instacart has finally filed their long-rumored S-1. The company exemplifies the kinds of startups that were built in times of capital abundance—growth investors are rarely excited to underwrite a business that hires 600,000 people to perform a repetitive task like picking items off grocery store shelves and delivering them.[1] But that activity has to happen no matter what if groceries are going to get from store shelves to consumers' refrigerators. Instacart hires delivery people directly, but the rest of the industry "hires" its customers to handle last-mile delivery in exchange for cheaper food. What Instacart gets from this is a unique data asset: it knows consumers' ordering patterns, knows the cross elasticities of demand across different products and categories, and can capture the upside from consumers trading up or trying new brands via ads. So you can think of Instacart as being somewhere between two different businesses:

- It's the worst grocery business imaginable because it takes a large-but-invisible cost—the opportunity cost of physically going to a store, loading up a cart, and getting it home—with an explicit cost that shows up in the prices of individual items and of delivery. This cost is 8.2% of their gross transaction value, excluding tips. Operating in an industry where mid-single digit margins are a sign of success, starting with a high single-digit cost disadvantage makes for a difficult path.

- It's the best imaginable grocery business because it can offer more breadth and can present every customer with a set of offers perfectly customized to a) get them to continuously shift more of their shopping onto Instacart's platform, and b) to get CPG companies to pay as much as possible for ads.

The synthesis is that Instacart raised a total of almost $3bn to pay the costs of the first model, and what they got in return was a business increasingly described by the second, where ads and recurring membership revenue continuously improve the margin profile of the company. In a way, it's another spin on Costco, whose model ultimately amounts to running everything as close to breakeven as possible so the only input is the capital expenditure to open new stores and the cash flow from those stores comes from selling new memberships ($).[2]

Instacart runs a many-sided network. In most network effect businesses, the smaller the number of node types the more likely they are to be complementary. For example, a restaurant booking app has two; it has an easier time recruiting restaurants if the app has lots of users, and to attract users if it has lots of restaurants. But as the N in “N-sided network” rises, the odds of network conflict go up. A simplified version of the business is that Instacart is a three-sided network where every participant complements the others: more customers mean more demand, more stores mean more supply, and more drivers mean faster and more reliable delivery. But there's a fourth category: Instacart also works with consumer packaged goods companies, which market directly to customers but which also market through stores, both by subsidizing stores' ads and by paying for prominent in-store placement. Kroger reported vendor allowances equal to almost $8.7bn, or 7% of revenue in 2017, before they stopped breaking this out, for example. That compared to Kroger’s operating profit of $2.1bn in the same year. So in a sense the default model for the grocery business is that an efficient, well-run grocery store will lose money on the business of selling food and other consumables to customers, but more than make up for it by selling direct or indirect ads to the companies that make those products.

How much can these ads be worth? Instacart's ad revenue is 2.6% of gross transaction volume. For some categories, it's hard to imagine ads driving much revenue—if you're selling staples to budget-conscious customers, they'll sort by price, and gross margins aren't especially high. But looking at price comparisons between Kirkland-branded products and comparable national brands shows that the price premium for branded products can be as low as 5% (coconut water) to as high as 131% (toilet paper). This post links to a Reddit thread where, among other things, Redditors who worked at Costco claim that the Kirkland products are identical to premium brands but have different packaging. In theory, a CPG company with a recognizable brand and a premium price should be willing to give up nearly all of the brand-driven incremental margin in order to get a customer to switch—if Ninja charges $100 more for the same cookware set than Kirkland, they come out ahead paying $95 for a customer.[3] Like many other online ad platforms, Instacart runs second-price auctions, where it's close to optimal for bidders to bid roughly the breakeven price for a given click, since they'll pay less than that if they win the auction and every win has positive expected value. That explains why their search page looks like this:

They're nudging customers towards commoditizing almost everything they want, and searching by category rather than by brand name. (There are some brand names here and there—it would be interesting to know how much Purina pays for that.) It's tempting to say that they've mitigated some of this channel conflict through financial relationships: they used to offer warrants to grocery stores, and Pepsi has agreed to invest $175m in Instacart at the IPO valuation. But that's really evidence of uncertainty about where value will be created and captured: both sides are implicitly buying schmuck insurance against the possibility that Instacart will permanently impair their pricing power.

This means that dealing with Instacart is a tricky problem for a grocery store. On one hand, they're getting a new source of revenue, and perhaps access to a new cohort of customers, which is valuable for a business with high fixed costs and where inventory turnover is essential. (Instacart notes in the S-1 that 16% of grocery sales are perishables, so when regular grocers can’t move inventory it goes in the dumpster.) They address this problem directly with Instacart Enterprise, a collection of e-commerce and analytics software products for grocers, as well as their "Caper Carts" smart cart. The Caper Cart in particular is an interesting tool, because it's something Instacart has an incentive to subsidize (it gets their brand and workflow in front of customers in the store) and that ultimately leads to more lock-in (leaving Instacart now entails buying non-subsidized not-so-smart carts instead).

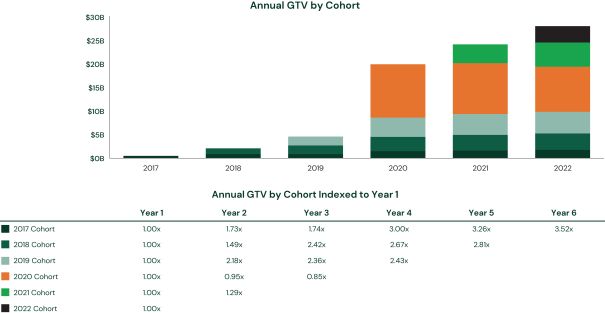

One thing that makes the business hard to evaluate, as with many other businesses, is Covid. They reacted reasonably quickly, promising to hire a quarter of a million new shoppers in April 2020. But this also makes their financials hard to read—a company whose biggest cost is unskilled labor and whose model benefits from channel shift to e-commerce is exactly what you'd want to own if you expected millions of people to be suddenly unemployed and hundreds of millions to be terrified of entering physical stores. But it also leads to the world's most annoying cohort chart:

This is a chart of six years, one corporate entity, but basically three different businesses. Early on, it's a classic growth story, where spending per customer keeps ratcheting up as early adopters find new use cases; their net dollar retention for their earliest cohort is 129% compounded, an amazing performance for a consumer-facing product whose industry saw 7% annual growth over the same time period. Then they had their massive Covid surge: eyeballing the chart, a majority of 2020 revenue came from customers who had never used the service before. Those customers were a unique group, though, and some of them churned out, either because they returned to their old shopping habits or compromised with a mix of online, in-store, and curbside. As the S-1 notes, they were also less likely to keep buying bleach and hand sanitizer by the gallon. And then we get to the last cohort with year-over-year spending data, 2021, and net dollar retention is—right back to 129%! But now they're in a more mature category, where far more people have at least tried grocery delivery, and where more of the large chains are handling it themselves.

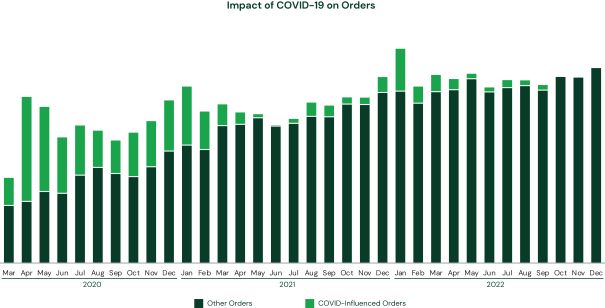

For what it’s worth, they do try to break out the impact of Covid, in what was no doubt a very fun data science project[4]:

Going forward, there are a few interesting drivers of Instacart revenue growth, including transaction fees, ad revenue, subscriptions, and store retention. They've grown transaction fee revenue faster than advertising revenue in recent quarters and years—ad revenue's share of total revenue in the first half of this year is where it was in the same period in 2019. But that's because of the interactions of a few different forces:

- Transaction revenue responded to demand faster than ad revenue during Covid, but it still took a while to catch up.

- Ad budgets stopped growing as fast as they historically have in 2022, a trend whose impact is most visible in the ad-heavy Q4 (ads were 35% of revenue in Q4 '21 and 30% in Q4 '22).

- They book a net revenue number after shopper payouts, and have gotten much more efficient in how they use shoppers. This cost reduction shows up as a transaction fee increase. From the filing: "Combined with other efficiencies, this has allowed us to decrease fulfillment costs per order from 10.2% of GTV in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 7.1% of GTV in the second quarter of 2023. Thus, these efficiencies translated into both higher profitability for Instacart and greater earnings for shoppers."

In the long run, transaction fees are a function of gross transaction volume, and based on the most recent cohort trends, that's still looking strong. If they're able to land new customers after the pandemic and see similar customer-level spending trends, there's still room to grow.[5]

Another complicating factor in the model is Instacart+, their membership program. For $9.99/month or $99.99/year, customers get free delivery on orders over $35 and lower service fees. Spending from these members is 57% of gross transaction volume, and members spend far more (6.2x over a five-year period, though there are strong selection effects here). The member count is still growing, from 4.6m to 5.1m over the last four quarters, implying that $510m of their revenue, or almost exactly 20%, is actually recurring subscription revenue rather than transaction- or ad-based.

Instacart+ partly makes sense due to the usual subscription economics of capturing consumer surplus in a fixed payment, enabling a lower marginal cost that enables a higher share of wallet. And that's interesting because of the ad business. By getting customers to sign up with Instacart+, Instacart is trading some variable revenue from the customer for higher order frequency, more searches, and thus more opportunities for ad revenue.

And there’s another great story on ads: they talk about adding "more emerging brands" among CPG advertisers, and Instacart does look like a good way for small CPG brands to rapidly scale. It's also a good way to increase bid density. Suppose there's some kind of search where the top advertiser bids $1 per click, but only needs to pay $0.05 because there aren't many or any other bidders. Adding one more advertiser for that query ratchets the winning bid up to the lower of whatever that advertiser bids or the $1 the first advertiser bids, so it's highly accretive.

One way ads show up long-term is in a higher revenue take rate, but the real magic happens at the gross margin level; it's just not much more expensive to run a fully-scaled ad business where every bidder is paying the market price for traffic than it costs to run a subscale one where some advertisers are getting an amazing deal. So it's more margin- than revenue-accretive. Gross margin shifts are happening overall, not at the cohort level: the most mature cohorts from different years all have similar gross margins in 2022. This is, indirectly, somewhat bearish for the ad revenue case. 2019's cohort had a gross margin of 6.5% in 2022, compared to 6.2% for the 2020 and 2021 cohorts, indicating that another year or two of first-party data only adds around 20 basis points of margin from better recommendations and better ad targeting.[6]

A final piece of the puzzle is retailer retention. Instacart's incentive is to follow the Shopify-style "arming the rebels" strategy: Instacart can invest in products that make sense for an 80,000-store base, about 16x the size of the proposed Kroger/Albertsons amalgamation. But every chain that works with Instacart knows it's ceding some customer information, some brand recognition, and some lock-in. The convenience of being able to order a particular brand of mayo directly to your door without getting up from the couch necessarily reduces the value of a big store footprint, and means that customers can be indifferent about whether any specific store has a great selection so long as someone in the Instacart service footprint has everything they want. Their top three chains are 43% of revenue, which is a lot of dependence on customers who are all continuously re-underwriting the relationship.

And really, all of these are part of the same question. Instacart might be the most challenging business imaginable: operating in a low-margin category with a cost disadvantage, coordinating a four-sided network where some sides have opposing interests, not to mention running a time-sensitive last-mile delivery network (dinnertime can be entirely dependent on when the Instacart order arrives!) dealing with fragile goods. Instacart's S-1, like many others, has some nice-looking graphics at the start highlighting all the impressive numbers behind their business. It's easy to imagine applying a similar design flair to a slightly different set of SQL queries to enumerate how many bruised peaches, cracked eggs, fat-free for full-fat fat-fingered substitutions, more-wilted-than-expected cabbages, etc. they've been responsible for. That's inevitable in this line of work, but it takes some high ad CPMs and Instacart+ retention rates to make it all worth it.

Instacart's IPO represents a positive change for tech. This is not the only company that was a viable IPO candidate in 2021 as a cash-burning growth story and is still a viable candidate today because they've managed to achieve positive GAAP earnings and a more sustainable operating model.[7] And, in fairness, their accumulated deficit is just $735m, and was $1.4bn at year-end 2021. As capital-intensive as the business could theoretically be, they built an impressive company without burning too much cash. Companies can never go public at peak certainty. (Actually, peak certainty is when private equity buys them, in order to convert that certainty into a higher debt/EBITDA ratio.) So they haven't answered every question. But they have answered one: a growth-oriented "full-stack" company with immense operating complexity can, in fact, get its house in order and turn into a profitable business that still has a growth story ahead of it, and can do that in time for an IPO.

The fact that this is hard to pull off without lots of agonizing ops work is fractally true: Instacart was originally rejected from Y Combinator, but got a last-minute interview by using their product to send Garry Tan a six pack of beer. ↩︎

This comparison is deeper than noting that both of these companies operate in an existing industry but have unusual economic drivers: there are more granular similarities. One nice thing about the Costco model is that it collects data on where customers live, and can compare that to general demographic data about neighborhoods, like average household income, in order to identify places where a new stores would increase spending from existing Costco customers who have a more convenient shopping destination and attract new customers. ↩︎

In practice, the ad revenue won't get quite that high, because the branded companies have pricing power in part because of brand, rather than direct response, advertising. Costco can focus on pure direct response ads to existing customers; repeatedly being in the news for keeping their hot dog and soda combo at $1.50 is the kind of positive media exposure that costs a lot more than the margin hit. ↩︎

In case you're curious, either as an investor or as an e-comm business owner trying to figure out how much of your 2020-21 revenue acceleration was caused by the pandemic rather than your own efforts, their process was to adjust for changes in their promotions and the regress shopping trends against Google's Covid mobility reports and case counts. There are two reasons they made this chart. First, it is a genuinely important question for investors to answer, and second, it's a way for them to show a pure up-and-to-the-right graphic when the one-time impact of the pandemic led to growth flattening out over the last eighteen months or so. ↩︎

On the other hand, net revenue retention-based models can decay and lead to massive re-rating in the underlying company. The S-1 actually demonstrates how fast that can happen: Instacart's Snowflake spending roughly doubled year-over-year in 2020 and 2021 (reaching $51m, or 2.9% of all Instacart opex), but is projected to drop more than 70% this year. Growing alongside customers is all well and good until those customers decide to start thinking harder about their costs! ↩︎

If we attribute all of this to ads, it's still something; since ads are 2.6% of TPV, it implies that more mature customer cohorts produce ~8% higher ad gross profits. But in an ideal world you'd see continuously improving gross margins for the most mature customers specifically because every additional purchase helps them target ads better. ↩︎

One side note on this offering is that it's a triumph for the alternative data industry. Many companies cite industry research from large legacy providers, like Nielsen, Gartner, and ComScore. But this appears to be the first S-1 that cites an alternative data provider, Yipit, by name as a source for industry information. Nielsen has a more recognizable brand, but for particular kinds of data—in this case, grocery ordering market share by average basket size—Yipit has the better data. ↩︎

Diff Jobs

Companies in the Diff network are actively looking for talent. A sampling of current open roles:

- A systematic hedge fund is looking for researchers and portfolio managers who have experience using alternative data (NYC).

- A company building ML-powered tools to accelerate developer productivity is looking for a mathematician. (Washington DC area)

- A well funded seed stage startup founded by former SpaceX engineers is building software tools for hardware engineering. They're looking for a full stack engineer interested in developing highly scalable mission-critical tools for satellites, rockets, and other complex machines. (Los Angeles)

- A company building the new pension of the 21st century and building universal basic capital is looking for a product manager with fintech experience. (NYC)

- A crypto proprietary trading firm is actively seeking systematic-oriented traders with crypto experience—ideally someone with experience across a variety of exchanges and tokens. (Remote)

Even if you don't see an exact match for your skills and interests right now, we're happy to talk early so we can let you know if a good opportunity comes up.

If you’re at a company that's looking for talent, we should talk! Diff Jobs works with companies across fintech, hard tech, consumer software, enterprise software, and other areas—any company where finding unusually effective people is a top priority.

Elsewhere

New Cities

A group of tech investors is buying land in Solano County, near San Francisco, with the aim of getting land rezoned in order to build a walkable city. There's a sense in which landlords in cities with strict land use rules are the residual claimants on all wealth creation, which makes the amount of market cap created by SV-based companies all the more impressive. Diluting the real estate price impact of wealth creation is a valuable goal, since one pathology of real estate wealth is that it simply doesn't take much effort to maintain, which leaves lots of time for sitting in SF Planning Commission meetings. The people paying rent tend to be busier.

Scraping

Kieran McCarthy has a good piece on how some of the companies that most aggressively restrict web scraping on their properties happily profit from it elsewhere. It's a nice Coasean parable: when there's a new property right—the right to the economic benefits of content you've created, or the right to the economic benefits of aggregating that content without owning it—there will be a period of extreme uncertainty while property rights get defined, and then a land rush once those rights are defined but mispriced. This tends to happen more with digital goods, because transaction costs are so low and scaling is so straightforward. One equilibrium is that the legal status of scraping stays uncertain, and companies use paywalls and restrictive terms of use to enforce their rights. That's a high transaction-cost environment, with benefits to scale (if OpenAI makes money from the NYT's content and from mine, the NYT is probably going to capture a larger share of the total wealth created). The other alternative is to rethink IP based on the new incentives AI creates.

Klaviyo

The Diff only had time for one S-1 teardown this weekend, but Matt Turck's writeup on marketing automation software company Klaviyo is worth reading as well. One notable piece of this is the ecosystem: Kalviyo gets 78% of its ARR from customers who use Shopify, and has signed a deal with Shopify that includes revenue sharing and an equity interest. Meanwhile, Shopify is a competitor. It's another case where schmuck insurance is a nontrivial problem: the equity and revenue sharing pay off best when Klaviyo captures more value relative to Shopify, but that's also the point at which cooperation is a worse deal than Shopify pushing its competing product and trying to squeeze Klaviyo out.

Crowdfunding

Launching any product can be modeled as a bet, ad for physical products the minimum ante is whatever inventory level is required to support the expected amount of sales and whatever marketing budget is likely to make those sales happen. The relatively high cost of betting on a physical product compared to a digital one amounts to a tax on new products. But there are ways around this: some large manufacturers, including Haier-owned GE Appliances, are experimenting with crowdfunding for new products ($, WSJ). This doesn't eliminate risk, but means there's slightly more information one step earlier.

Maturity Matching

A good rule of thumb in finance is that it's much safer to borrow when the length of the loan roughly matches the useful life of the collateral. Borrow too long-term, and you're paying a higher interest rate than necessary for longer than you need to. Borrow too short term, and you're betting your entire business on being able to roll over the borrowing. One fun example of this is Japanese whisky and sake breweries borrowing long-term against casks that take a long time to age ($, Nikkei). This distils credit down to its essence: there's one kind of uncertainty that can't be eliminated, that of what demand will look like in twenty or thirty years. But one kind of uncertainty, about what funding markets will look like over the time that a brewery needs to hold inventory, can be eliminated.

Byrne Hobart

Byrne Hobart